A sow with two older cubs digging for caraway and foraging for clover.

Wrapping-up

As my summer comes to a close, I reflect on the last two seasons I have spent in Tom Miner Basin. There have been many lessons learned, sights seen, and memories made. I will forever cherish the morning rides through the landscape with the excited anticipation of not knowing what is to be found. I am grateful that I got to experience two completely different years and multiple seasons. Last year was incredibly wet, green, and lush. It was normal for it to rain almost every afternoon, and fires never once crossed my mind. I have pictures of a pasture in September last year and it was more vibrant green then, than it was in July of this year. This year we are thinking about more than just predators. Fires, shade, water, and grass are all being discussed on a regular basis as we are experiencing extremely hot weather and lightning storms. So far, it has been manageable, but I know everyone, including myself and the cattle are welcoming the upcoming cooler weather.

A relaxed herd.

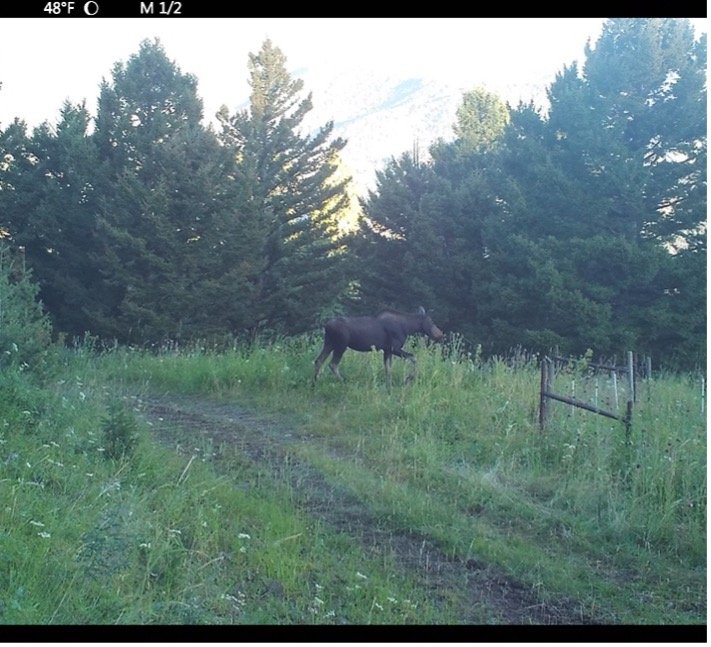

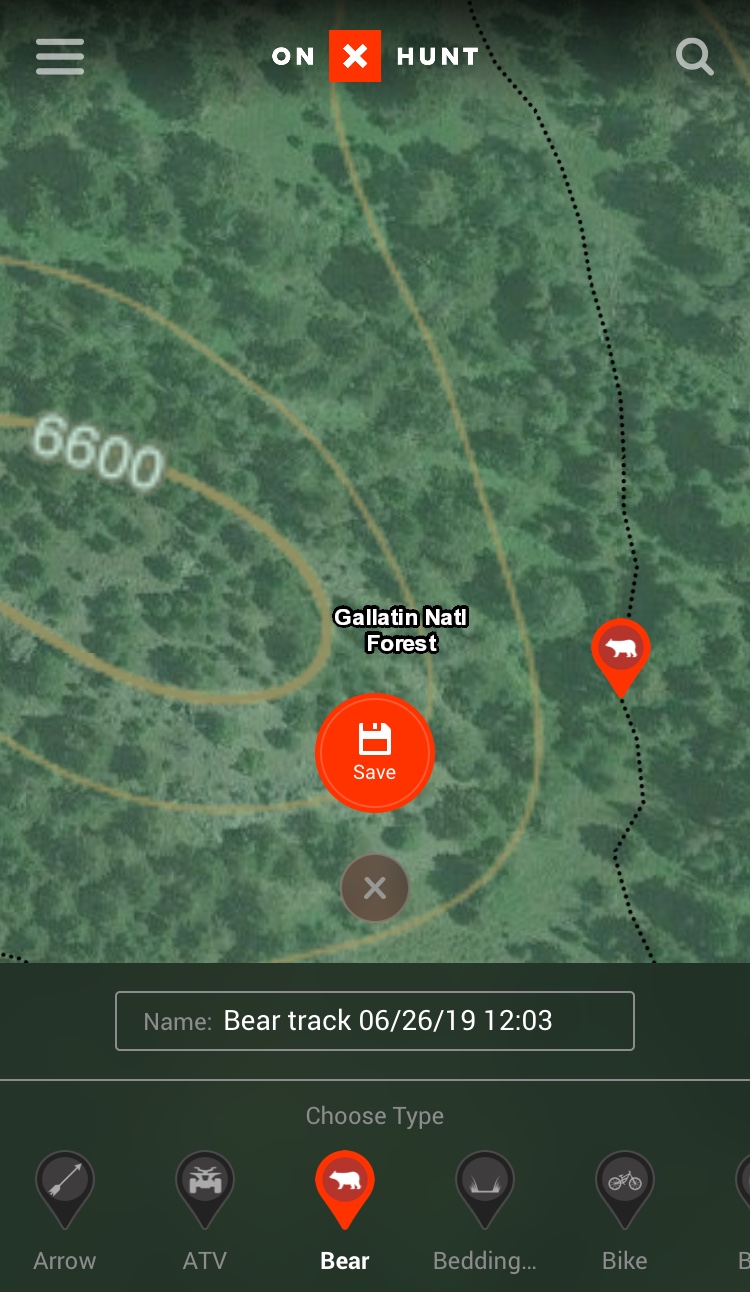

Bear activity has been interesting to contrast between years. Last year, I maybe saw 5 or so bears on rides total and this year I have seen 2-6 bears almost every single ride for the last three weeks. It is a good reminder than not every bear kills cattle, it is just a small handful that need to be dealt with effectively. Most of the bears I have been seeing are either sows with cubs or different groups of subadults traveling together, but I have seen the occasional large male. I have noticed the elk have come back in large herds, when last year they pretty much stayed away until the Fall. Also, I was lucky enough to see wolves this year, and I never saw any last year. I have only seen one moose and her calf, when in 2023 I saw several moose throughout the summer. Overall, there has been a fair amount of wildlife on the land.

Getting ready to move cows with the intense smoke and a storm brewing.

Wrapping up my time here has brought up many emotions, and many memories. I have compiled a list of some of the lessons I have learned while being a range rider. While this job takes many forms depending on how you make it your own, these are some of the tidbits I have picked up along the way:

When your horse stops and swears something is there, believe them

If there is a cow off by themselves, there is most often something wrong or worth investigating

If you ride long enough along a fence line, surely there will be a gate somewhere, or so you hope

Listen to the cattle, they can tell you a lot about what has happened in the pasture, and whether or not there is something to worry about

As soon as you become lost in your thoughts, you are likely to see a bear

If you hear short bursts in the trees from an air compressor (that is not an air compressor), it is a spooked bear

Listen to your instincts, if you get a bad feeling about something, get out of there. Likewise, if you get a good or curious feeling, pursue it

I have become an expert at rancher directions, for example: “So you’ll keep riding along the East fence line until you hit the big broken aspen. Once you feel the wind change directions you will follow the trail that the cows made back in 1998 until you hit the spot where that thing happened, remember that? Once you see the water tank it’s another two miles through thick timber until you hit a small gate, ya can’t miss it. If you do miss it, give me a call (there is no phone service)”

When they tell you the biting flies “only last two weeks”, buckle up for at least a month of insect torture

At the ripe old age of 27 I groan and croak every time I hop off my horse to get a gate

Many people fear grizzly bears more than any other animal on the landscape, and often what comes with that fear is false bravado and a conquerors mindset. Truly, they mostly just fear the unknown

In remote areas, yelling “hey bear” long enough has the added benefit of alerting the cows to your presence, and if you get lucky, they will call back

Yearling cattle move like schools of fish, everywhere, all the time, and through any weakness there may be in a fence

That low guttural growl you hear? Although that instinct is telling you it’s an angry bear, it is just the half-hoarse bull in the herd trying to find his ladies

Always bring some extra bailing twine, it can fix just about anything in a pinch

Nothing can prepare you for how amazing seeing a pack of wolves is

Is that a cow or a bear? From far away the big black dots are pretty hard to tell apart. Look for the shoulder hump or a tail swish before moving forward

Being alone allows you to tune into everything on a much deeper level than when another human is around. I find all of the most interesting things when I am completely alone

While I am usually alone in terms of people, I very rarely feel lonely thanks to the great dogs and horses that help me do my job

Lastly, good communication is the key to everything. With your horse, with the producer, with the community. Maintaining a constant and clear line of communication with these parties really makes all the difference in building positive relationships and making sure the job gets done

I may be signing off as the Tom Miner Basin range rider, but a piece of my heart will always be attached to this place and this work. Though I have a busy few years ahead of me, I know that the basin will draw me back.

-Ellery Vincent

2023 ’24 Range Rider

A coyote moving through a pasture.

A herd of elk grazing.

A bull elk in the evening.

A short-tailed weasel checking me out.